|

|

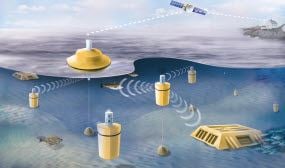

Networks could consist of communication nodes to which core sensors can later be connected; e.g. small echo-sounders. The nodes could be moored to the seabed or function as unattached “floaters” that drift with the current. (Illustration: Bjarne Stenberg) |

Last year saw the launch of the cooperative project on “A New Nervous System for the Arctic”, with a budget of NOK 21 million.

Kongsberg Maritime, Fugro Oceanor, Statoil, Western Geco, the Institute of Marine Research and NTNU/SINTEF want to monitor the ocean in the same way as the surface of the Earth and the atmosphere are being monitored today.

Environmental monitoring, biomass monitoring and greater certainty regarding petroleum pipelines and offshore installations are among the benefits envisioned.

Monitoring the entrance

Everyone involved realises that the Barents Sea is huge and that it would be impossible to cover it completely with a wireless network. However, the Institute of Marine Research has a vision of placing sensors and a monitoring system along the line of the continental slope to the north of Troms, for example, where the seabed makes a sudden jump from deep to shallow.

If we manage to monitor the “entrance” to the Barents Sea, we have the prospect of obtaining unique data. Fish from the Vestfjord heading for their spawning grounds in the Barents Sea would have to cross this line, as would plankton drifting eastwards with the ocean current.

An innovative approach here would at least cut down the expensive cruises in which research vessels cross the ocean to collect samples of stocks.

Arctic network of sensor nodes

The idea is to deploy communication nodes to which core sensors can later be connected; e.g. small echo-sounders. The nodes could be moored to the seabed or could function as unattached “floaters” that drift with the current. A third possibility would be to install them on small underwater vehicles (ROVs), if something in particular is to be studied within a limited area.

“We can also imagine locating units on surface buoys to enable the network of sensors to communicate via satellite”, says SINTEF scientist Knut Grythe. “Fugro Oceanor, with its buoy expertise, is interested in setting up wireless communication with its products – with a view to international use.”

Communication in the Barents Sea can thus take place both through an underwater network for internal communication, and to the rest of the world via buoys floating on the surface. When subsea petroleum installations are to be monitored, we might also use existing communication cables between the network and the outside world.

Talking underwater

Only sound can be used to communicate under water, and Knut Grythe and his colleague Tor Arne Reinen are currently working on the problem of making sound travel efficiently from one point to another.

In an internal project they have established an acoustic link about two kilometres long in the fjord outside Trondheim, and have installed two microphones at one end and two loudspeakers at the other.

“This ‘multiple input/multiple output’ (MIMO) setup is relatively new as an underwater system, and we have little experience to fall back on”, says Grythe. “The system can help us to communicate more reliably and with a higher rate of information transfer than before. It will be rather like when people install a broadband router at home, but with two antennae instead of one.”

However, the scientists also have to deal with other challenges to communication. Sound tends to travel slowly under water. When a signal is transmitted, it is almost like having a radio receiver on Earth and a transmitter on the Moon. Another problem is that the route taken by the sound varies with temperature and salinity as the seasons change.

“We can think of sound dissipation under water as a fan of sound beams. Some of the beams are deflected down into the sea while others are deflected towards the surface. This makes our work even more complicated. We need to create ‘smart signals’ and robust receivers”, explains Tor Arne Reinen.

The scientists are borrowing methods and technology from mobile telephony among other areas, and the principles will be tested in the course of the coming year.

“If we can identify good solutions for our distance of two kilometres, we can then scale them up to real conditions”, says Reinen.

The fjord as a laboratory

On the NTNU side, Professor Jens Hovem has been a central person and visionary driver of the project. Together with Yngvar Olsen at NTNU’s Biological Station, and a core group of scientists, he has promoted the idea of the Trondheim Fjord as a broad, interdisciplinary research platform.

“A need has emerged for a marine laboratory in which different groups can work together. We have formed a work group that is drawing up a description of such a laboratory right now. It is necessary to bring together people from SINTEF and NTNU – and from different disciplines such as biology, ICT, archaeology and marine environmental science.

Many people need to model things, and we can envisage a test-bed on which we can place equipment on a small scale in order to take our first shaky steps on home ground”, says Olsen.

Åse Dragland