By Otto Lunder, senior scientist, SINTEF

Professor Kemal Nisancioglu, NTNU

Merete Hallenstvet, senior engineer, Hydro Aluminium.

The formula for successful industrial research is a long period of hard work, laying stone upon stone. Many years of research collaboration by Hydro, SINTEF and NTNU, with the essential financial support of the Research Council of Norway, are a good example of this formula.

These efforts have made an important contribution to the respect that recycled aluminium enjoys as a material for façades in Europe.

Now we are doing research into how to deal with future phases of the recycling story.

Energy-saving

|

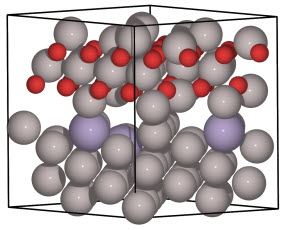

| Aluminium panels at atomic level: A glimpse beneath the surface of aluminium façade panels. The computer model shows the surface between the metal and the outer layer of oxide that protects it against rust. The grey spheres are aluminium atoms, the red are oxygen, while lilac represents foreign atoms. Foreign substances occur in all aluminium products. Calculations show that the most stable position for large foreign atoms is actually on the surface, where there is most room for them. Illustration: SINTEF Materials and Chemistry |

Since the early 90s, recycled aluminium has been an important raw material for Hydro’s rolling mill in Holmestrand.

Everything from building scrap to used aluminium pots and pans is brought to the mill from many European countries.

Remelting scrap aluminium requires only five per cent of the energy needed to produce new aluminium.

This means that recycling can reduce the greenhouse gas emissions caused by aluminium production by as much as 95 per cent.

However, it was not a foregone conclusion that remelted scrap aluminium could be turned into smart, unblemished panels for building façades, because in 1990, something unfortunate happened to a prestige building project in the Netherlands.

Cosmetic, but serious, problem

The building had been clad in panels of new extruded aluminium. Aluminium is known not to “rust”, because a fine layer of oxide forms on its surface immediately after processing, and this protects the metal.

However, the external surface of the high-prestige building in The Hague did rust, creating bubbles in the protective finish.

Although the problem was purely cosmetic, and did not affect the safety or operation of the building, it was serious enough.

Important knowledge

A subsequent project in which SINTEF, NTNU and Hydro participated showed how aluminium façade materials must be pre-treated before they are painted. Armed with this important knowledge, the European aluminium industry was able to prevent a repeat of the “Hague nightmare”.

In Norway, we continued to do research in order to be quite sure that cosmetic rust would never be a problem for façade panels of recycled rolled aluminium from Holmestrand.

In these studies we used a transmission electron microscope (TEM), which showed us that rolling deforms the outermost layer of material on nanometre scale (a nanometre is the amount by which a fingernail grows per second), and that this could cause the protective oxide layer to fail. So the Holmestrand rolling mill developed a surface treatment that removes the deformed layer.

“Collecting site” for trace elements

|

| Closing the circle: Aluminium scrap, remelted at Hydro Holmestrand, has been turned into a beautiful façade and roofing material for Rumania’s most modern football stadium – the home ground of CFR Cluj. Photo: Pal Szilagyi-Palko / Demotix / NTB SCANPIX |

Our TEM studies also showed that the deformed surface layer also functions as a “collecting site” for trace elements – tiny amounts of foreign atoms that are found in all aluminium materials.

We realised that these increased the risk of “cosmetic” rust. With the removal of the surface layer, the rolling mill also removed this risk.

Competence-development project

All aluminium products contain alloy metals and trace elements. If the content of foreign materials is too high for what the scrap will become in its next phase of existence, this can be counteracted by adding new aluminium during the remelting process.

But what about the future?

What if scarcities of energy and resources mean that one day, we are forced to reduce the proportion of fresh material to the melt? Could this result in problems with the surface of façade panels of recycled aluminium?

We are currently looking at this aspect via a competence-development project supported by the Research Council of Norway.

Showing the way to counter-measures

In laboratory trials, we have increased the content of the relevant trace elements in rolled aluminium, and we have found that this can trigger cosmetic rust, even if the surface layer is removed.

It is true that we still have to see whether different trace elements cancel each other out when several of them are present in the alloy. At any rate, the findings show what kinds of surface treatment the rolling mill can employ to counteract these effects, just to be on the safe side.

What we have achieved since the start of the project would not have been possible without several years of support from the Research Council of Norway. In a world that needs to save energy, recycling will become more and more important. Norway has a great deal to contribute here, but to do so we need to continue our programme of long-term research and development.

This article was previously published (in Norwegian) in Dagens Næringsliv (January 11, 2013).