In the early 1950s the Norwegian wild lobster catch amounted to about 1000 tonnes per year. Today this figure has been reduced by 95 per cent. This drastic decline has resulted in the release of juvenile lobsters as part of sea-ranching programmes.

The animals come from Norsk Hummer AS’ facility at Tjeldbergodden. The company has been working for something over 20 years, together with SINTEF among others, to find the best system of farming this unique species.

Heat is the key

”In nature, development rates among lobster larvae are determined by water temperature”, explains SINTEF researcher Jan Ove Evjemo. “In spite of the fact that a female lobster can produce as many as ten thousand larvae, total production along the Norwegian coast is relatively low. This is due to low water temperatures and high predation rates by other crustaceans and fish”, he says.

This is why at Tjeldbergodden surplus heat from the methanol plant is used to create optimal conditions for these fastidious creatures. If all goes to plan, they will end their lives as well-nourished wild lobsters.

Doubling survival rates

”We have shown that it is possible to double larval lobster survival and boost their growth rates”, says Evjemo.

Up to now the problem has been that only relatively few survive the larval stage. The animals are very picky about their food, and will exhibit cannibalistic tendencies if food supplies are low or disappear. Thus the biggest challenge faced by researchers is to find the optimal first feed. They are now on the point of a breakthrough which could result in major increases in larval production.

”Firstly, we have reduced the cannibalism problem by means of experiments with new feed”, says Evjemo. “At the same time we keep the lobster larvae in a bath supplied with air bubbles and this prevents them from getting too close to each other”, he says.

Aquarists take the lead

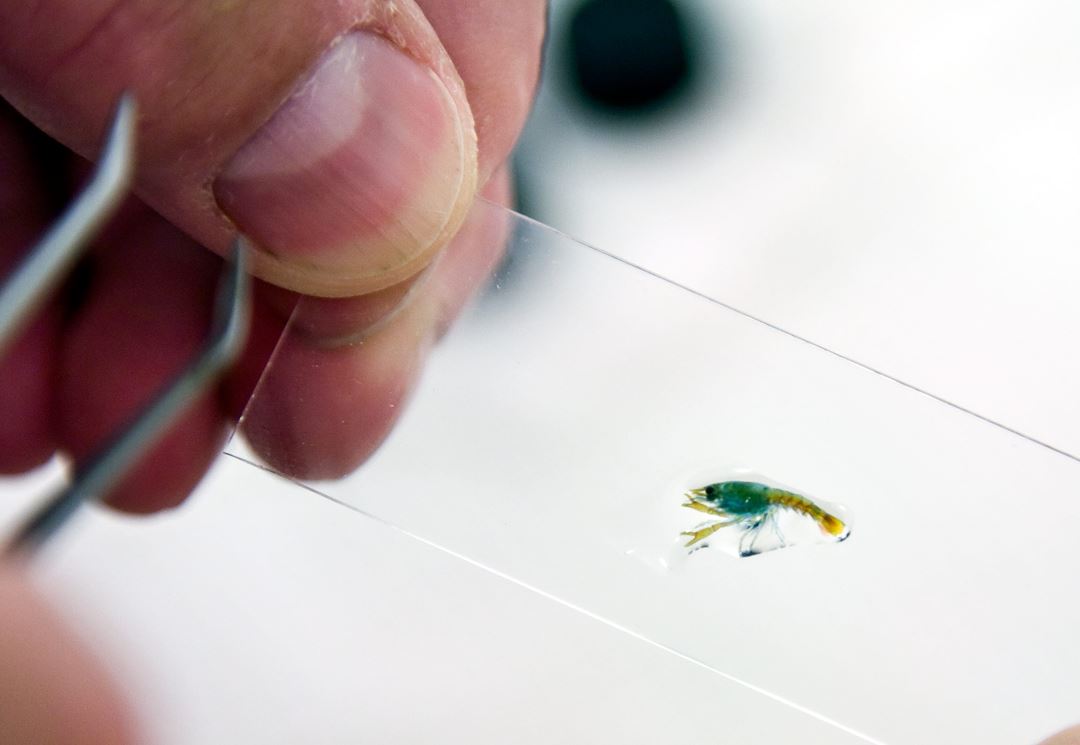

Researchers conducted an experiment involving separating 600 newly-hatched lobster larvae into three groups. Each group then received its unique first feed and plenty of space. Two groups were either given the traditional live feed organism Artemia, or a wet feed. The third group was given live copepods (Acartia tonsa). This is a small crustacean which SINTEF has previously tested as a first feed for problematic farmed species and rare aquarium fish species.

After eleven days major differences were observed. Lobster larvae fed with live copepods exhibited survival rates ranging from 20 to 40 per cent better than their peer “competitors”. Their development was also more advanced.

A new industry

SINTEF’s experience using copepods as first feed for a number of marine fish species, and now also lobsters, is encouraging enough for us to start planning the production of live feed species on an industrial scale.

”We believe that this could become an important supplement for the marine aquaculture industry which currently uses copepods as first feed for species such as wrasse”, says Evjemo. “Wrasse are currently used as our ”ecological weapon” in the fight against salmon lice, since the wrasse graze on the lice which are attached to the salmon”, he says.

The project is funded by VRI Møre og Romsdal and Norsk Hummer AS.

CHRISTINA BENJAMINSEN