Household bacteria thrive on the walls and ceilings of dairies, and can also be found in raw milk and cheese-making equipment. These bacteria are among the causes of minor differences in the taste of a given type of cheese, depending on which dairy it was made in.

However, TINE, the sales and marketing organization for Norway’s dairy cooperative, is now planning an in-depth study that will find out whether such “stowaway” organisms can be used for their own sake. Many cheeses are matured for eight weeks before they are ready for sale, and dairies evaluate them on the basis of their appearance, odour, flavour, consistency and their “eyes”, or holes.

It is essential that these new household bacteria should have positive effects, and the company has therefore drawn up a list of ten characteristics that it wishes to identify. If household bacteria with these desirable characteristics are found, they will be added to new or existing cheeses.

Department manager Jorun Øyaas of TINE says that exploiting the properties of household bacteria has recently become particularly relevant because the company is in the process of building a large new dairy in Jæren in southwestern Norway. The new plant will mean the closure of four small dairies in the county of Rogaland.

“We are going to try to preserve cultures of these household bacteria before the old dairies are shut down,” says Øyaas.

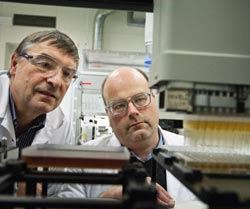

LABORATORY TEST: Nils Dyrset (left) and Geir Klinkenberg of SINTEF Materials and Chemistry are studying and culturing bacterial colonies in the laboratory in order to identify their positive characteristics.

Photo: Thor Nielsen

Click to open

Hunting for bacteria

TINE has brought SINTEF and the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) into the project. UMB Professor Siv Skeie has been accumulating knowledge of household bacteria for use in the project, while SINTEF runs a laboratory that is equipped to seek out, cultivate and study large numbers of bacterial colonies simultaneously. This last aspect will be an important part of the project.

“Large numbers of bacterial organisms need to be tested, and we will be looking for between five and ten specific characteristics, a process that will involve a very large number of tests. Our screening laboratory enables us to efficiently screen many bacteria in parallel,” says SINTEF’s Geir Klinkenberg. “We can combine efficient analyses with efficient cultivation on a very small scale. The use of automated equipment reduces the chances of human error, which is often a problem when we are dealing with large sample sets.”

The two partners are already well under way with their efforts, and have been sampling cheeses for about a year, both from the four Rogaland dairies and from other sites.

“We use mature cheese, and take out small samples which we make into a loose mass. This is spread out in Petri dishes that contain a culture medium in which the bacteria can grow,” says Nils Dyrset, also of SINTEF.

The scientists have now started to take samples of the cultures and select bacteria that look promising. The bacterial flora are characterized on the basis of their desired characteriztics – before possibly being taken on to the next stage.

Stable cheese

The project, which will continue until 2013, is being financed by the Research Council of Norway and the dairy company to the tune of NOK 7–8 million.

“We are basing the project on some of our own types of cheese,” says Jorun Øyaas. Our aim is to consistently produce a top-quality cheese that is more stable no matter which dairy produces it.”

All the same, we may also find bacteria that give us a special product, which would be an extra bonus for us!

Åse Dragland